[By Sreshta Ladegaam]

“Women still experience the city through a set of barriers—physical, social, economic, and symbolic–that shape their daily lives in ways that are deeply (although not only) gendered,” writes Leslie Kern in her seminal work ‘Feminist City’. These barriers are universal and are responsible for denying women opportunities that could help them break free from years of subjugation.

In Hyderabad, Shaheen Women’s Resource and Welfare Association has been working to help women step out of the confines of their homes to study, work, or just walk the streets at leisure. Founded in 2002 by activist and poet Jameela Nishat, Shaheen began with the mission to help women and girls restore their sense of identity and dignity and achieve socio-economic stability. Shaheen’s crusade against trafficking and gender-based violence has been highly recognized, winning them the Martha Farrell Award for Gender Equality in 2021.

Headquartered in Sultan Shahi, in the heart of Hyderabad’s Old City, Shaheen’s work spans 25 bastis. At the core of this organization lies a group of resilient women, many of whom are survivors of gendered violence. They have been working diligently towards the empowerment, safety, and mobility of women over the past two decades.

Mehendi classes at Shaheen

To truly comprehend the impact of Shaheen’s efforts, one must understand the intricacies of the Old City as an urban space with a complex history. This part of Hyderabad is home to iconic heritage sites like Charminar, Chowmahalla Palace, and Qutub Shahi Tombs, among others. Founded during the era of the Qutub Shahi dynasty and further developed under the Nizams, the region now stands as a testament to the city’s diverse heritage. The present-day Old City showcases a vibrant blend of cultures, with approximately 65% Muslim residents, 30% Hindus, and the remaining residents representing various minority religions.

The current city of Hyderabad expanded well beyond the boundaries of the Old City. Once predominantly inhabited by Muslims, Old City experienced a shift in demographics due to the influx of non-Muslim, primarily Hindu immigrants, following the annexation of the Hyderabad state and the subsequent designation of Hyderabad city as the capital of Andhra Pradesh. The disturbances caused due to these changes were exploited by political parties and other vested interests during rapid urbanization through the ’70s until the ’90s, especially in times of political and religious turmoil in the country, fueling frequent instances of communal unrest.1 Gruesome gendered violence was rampant during the riots, bearing grave consequences for women’s safety and mobility in the region going forward.

Furthermore, modern expansion efforts in Hyderabad have overlooked Old City, focusing on developing newer areas like the IT hub of HITEC City. As a result, Old City has been excluded from crucial development plans, hindering its socio-economic progress.

Women in the region are disproportionately impacted by these factors, making it difficult for them to access employment and education. Areas in Old City that witnessed frequent communal tensions have had a noticeable increase in child marriages. Trafficking of girl children, within India and to the Gulf, became a persistent problem. The Shaheen team has successfully busted several Sheikh marriage and trafficking rackets in Hyderabad, preventing almost 1000 child marriages in the region. They have rescued and supported thousands of women and girls who were victims of trafficking and other forms of abuse, through counseling, legal assistance, rehabilitation assistance, and economic empowerment.

Although this aspect of Shaheen’s work is widely documented, very little has been written so far about their two-decade-long work of building an active network of women and girls across Old City, and affecting change through community-led action. Certainly, Shaheen’s rescue operations and interventions are not spontaneous actions taken upon hearing of individual instances of violence or abuse. Their success in affecting a positive change is rooted in their on-ground work through extensive home visits, awareness programs, and cultural advocacy.

The Shaheen team emphasizes the importance of taking a secular approach as they deal with Muslim, Hindu, and Dalit communities. Pooja, a field coordinator, says, “We dream of a society where nobody is denied a dignified life due to their caste, class, gender, or any other differences. We want to create a safe space for women where they can understand their rights and stand up for themselves.”

A Legal Counseling session by Ms. Devika at Shaheen Center, Amaan Nagar B

Apart from the central office at Sultan Shahi, Shaheen has three additional centers located at Hasan Nagar, Shaheen Nagar, and Aman Nagar B. These centers serve as entry points into the communities. They offer a range of vocational training programs such as tailoring, mehendi design, knitting, and embroidery work. They recently added computer classes to their offerings and maintain well-equipped computer labs. Courses on other skills necessary for employment like English language training and career guidance are also offered. Women and girls of all ages are welcome to join these classes. They also help people find jobs, further contributing to their efforts to empower communities.

Shaheen’s field coordinators conduct regular home visits and interact with families. These interactions are an essential component of their work, as these instances help them build trust with the communities they serve and give them an insight into the struggles and needs of women. The coordinators also talk to the family members and encourage them to support the women in attending skills training at Shaheen centers.

“Economic empowerment is the first step, especially for survivors of abuse. Once a woman is economically empowered, she can start making decisions for herself,” says Jameela Nishat, the founder of Shaheen. “But it’s a problem if she still thinks along the lines of patriarchy. There needs to be a change in her mindset as well,” she adds.

Field coordinator Sultana says, “Skills training ke zariye hum ladkiyo ko idhar bulathe hein center mein. Aur skills training ke saath saath hum awareness create karte hein (We encourage girls to visit the centers for skill training. Along with that, we also try to create awareness).” She points out that parents are usually keen to let girls learn vocational skills. “So we use it as an opportunity to educate them on other important issues as well,” she adds. Although economic empowerment is extremely essential, Sultana believes that they will not be able to bring about a long-lasting change unless a culture that enables the oppression of women is challenged.

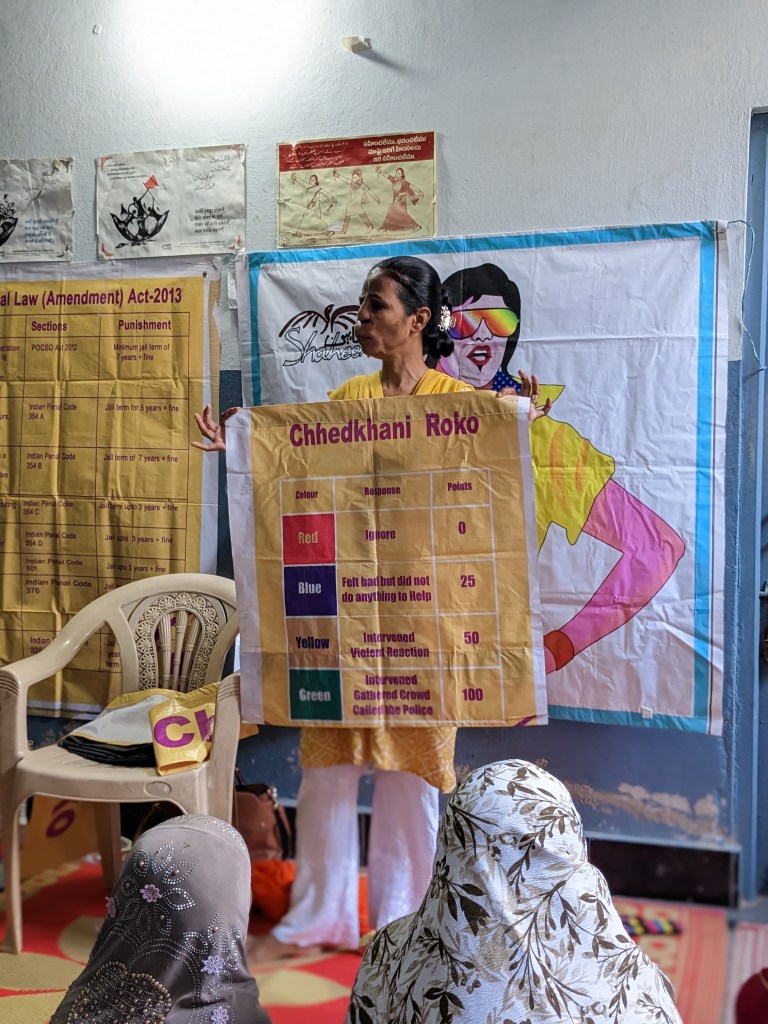

A Chedkhani Roko Session

Women and girls enrolled in the vocational training programs get to attend sessions on sexual and mental health, legal counseling, and more. These sessions are specifically tailored to address the needs of adolescent girls, helping them cultivate a positive relationship with their bodies and minds, recognize instances of abuse, and gain knowledge about their rights and legal procedures. Additionally, girls are encouraged to express themselves through art and guided imagery sessions.

The coordinators prioritize individual meetings with each girl attending the sessions, to grasp their specific challenges whether at home, school, or college. Sultana says, “Sometimes they are uncomfortable opening up about their experiences, so we frame our questions differently, such as asking – kya aap ke friends mein kisi ke saath ye hota hein? Aap refer kar sakte hein (Has this happened to anyone among your friends? You can refer them to us). We assure them that their identity will be protected if they report any incidents.” In this process, they have built large support networks of women and girls through whom they manage to find out about situations of violence and abuse and hold urgent interventions and rescue operations.

To further cultural advocacy, they organize all-women Qawwali performances and Melas with interactive games and stalls that discuss topics ranging from education to unpaid care work. Young boys are allowed to enroll in awareness sessions, computer training, and special gender sensitization sessions.

Shaheen also actively motivates women and girls who drop out of school or college and provides them guidance to appear for examinations through open schooling. So far, they’ve helped more than 4000 girls in Old City to return to school.

Guided Imagery, Activity, and Art sessions at Shaheen

Considerable effort is put into counseling the family members of the women and facilitating a shift in their mindset. Hasan Nagar, where Shaheen operates one of its centers, has a substantially higher number of dropouts among girls. A recurring concern raised by family members and women is the distressing lack of safety on the streets due to harassment and catcalling.

Sultana Begum, a 17-year-old from Hasan Nagar, had to drop out of school because of this unchecked harassment on the streets. She found out about the nearest Shaheen center through her friends and enrolled in tailoring classes. “I did not fight back when I was asked to stop going to school. Phir yaha aane ke baad humein pata chala padhai kitni zaruri hein (After coming here. I understood the importance of education),” she says. The team at Shaheen counseled her parents to let her continue her education. She has now completed her schooling and is a recipient of the ‘Shaheen Ratna Award,’ for encouraging other girls in her family to re-enroll in school.

It cannot be denied that men and women experience starkly contrasting realities when it comes to mobility and socialization in public spaces. While families often employ the fear of street harassment to further restrict women’s freedom, the dearth of effective measures to ensure safety has become an impediment to women’s right to access the city. The lack of safety on streets directly affects women’s education and livelihoods and further complicates their relationship with public spaces.

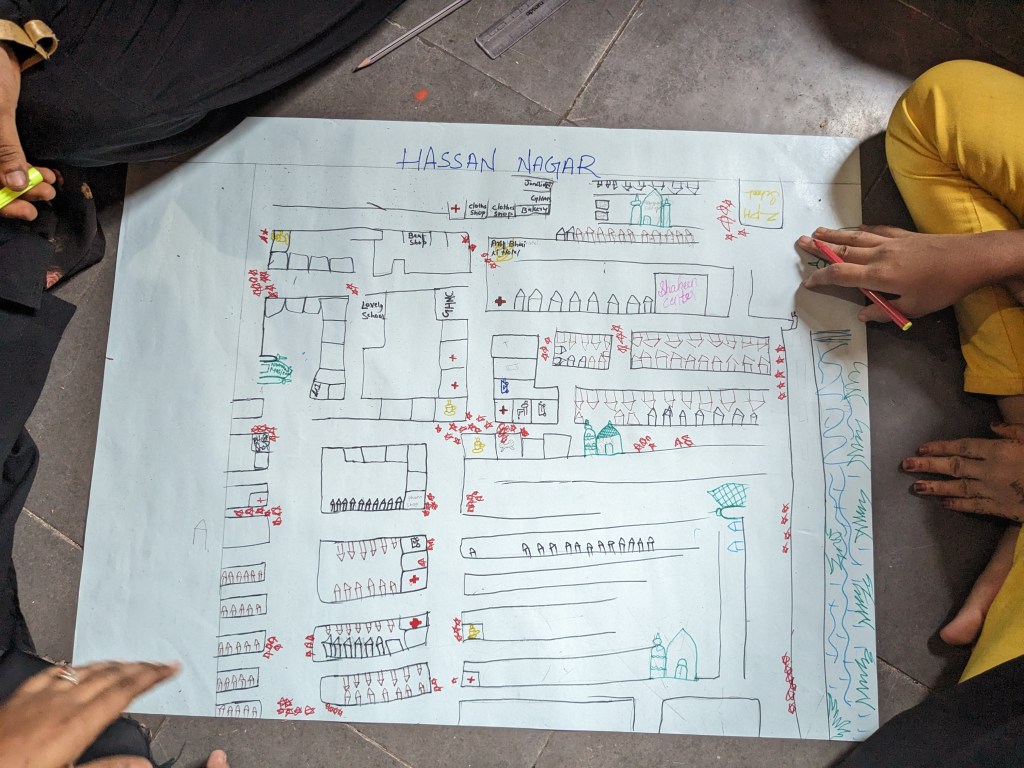

A Safety Map

Shaheen organizes ‘Chedkhani Roko’ (Stop Harassment) sessions to educate boys and girls about harassment on the streets. Jameela Nishat says, “A few years ago, a girl from a nearby school was stalked by a local goon’s son. He followed her all the way to the school and put her life in danger. She dropped out of school and her family moved away. This is when we decided to do something to make streets safer for our girls.” The Shaheen team managed to get the girl re-enrolled in school. This incident led to the idea of implementing an exercise called ‘Safety Mapping’ which is now a key aspect of their work towards ensuring the safety and mobility of women and helping them occupy public spaces without fear.

Safety Mapping is an interactive session where women and girls are encouraged to illustrate a map of their neighborhoods on a chart. They are prompted to identify and pinpoint the spots where harassment or cat-calling is frequent. Typically, these locations include chai tapris (local tea stalls), auto rickshaw stands, and busy junctions. These identified hotspots are marked by a vibrant red star symbol. A copy of the map is handed over to the nearby police station with a request for heightened patrolling at the hotspots.

A Safety Mapping Session

Zehra, one of the field coordinators, notes that the police haven’t always been sensitive to matters concerning women. The Shaheen team has been consistently working to make the police acknowledge and actively address women’s issues. “Due to our experience with the police, we do not name any names. We only request them to patrol the hotspots. Fortunately, we have been seeing a lot of change in recent years. Patrolling at the hotspots has actually helped to make these spaces safer,” she adds. In the absence of any sustainable mechanisms to make streets safer for women, the Shaheen team says this is their best bet. Safety mapping has yielded positive results for the mobility of women and girls.

Apart from safety mapping, they also conduct safety walks where girls from different communities are made to visit each other’s neighborhoods to erase the stigma and build communal harmony.

Another impediment to women’s mobility in Old City is the lackluster state of public transport. Funding cuts for TSRTC (Telangana State Road Transport Corporation) led to the discontinuation of many important bus routes in the region. Moreover, the proposed Hyderabad Metro Rail route extension to Falaknuma is experiencing unwarranted delays. As a result, women primarily rely on auto-rickshaws as their mode of transportation. However, the uncertainty associated with auto travel has prompted many female students and working women to choose two-wheelers instead. Recognizing this need, Shaheen recently started a free-of-cost two-wheeler training program for women and girls to facilitate their mobility.

Two-wheeler training at Sultan Shahi

A major setback to Shaheen’s work came with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic. The unprecedented lockdown measures had a devastating impact on women, restricting their movement and leaving them more vulnerable to gender-based violence and abuse. The team recollects the horrors women had to go through during this period. Field coordinator Zehra says, “There was an alarming rise in cases of child marriage, sexual abuse, and domestic violence. The numbers are still not going down. It’s like the pandemic opened up a can of worms.”

Sultana says, “So many people lost their livelihoods due to the lockdown. Schools and colleges were closed too. So all the family members were at home. Women had to work extra to ensure their needs were met.”

The Shaheen Nagar area of Old City gained particular notoriety in this period for a high incidence of gendered violence and sexual abuse against women. A new center was established in this area during the pandemic.

Although the head office at Sultan Shahi had to be closed from the outside during lockdowns, they were still open to address the needs of women. The team was actively working behind doors during this period. They created WhatsApp groups for women and girls in the region to make sure they could support them in times of emergency. They distributed rations for people in need, and through this process, continued to reach more women.

As the Shaheen team deals with the after-effects of the pandemic, they are working to ensure that they are ready to tackle such a situation going forward.

Discussing the future of Shaheen, Jameela Nishat says, “I want all women [in Old City] to be capable of not just empowering themselves but have the strength to support others and become leaders of their communities.” She envisions a future where women are no longer afraid to stand up against injustice and question the system.

As we reflect on the significant findings from Shaheen’s efforts, it becomes evident that large-scale institutional support for women’s issues remains lacking. While law enforcement has been providing assistance, the field coordinators themselves have acknowledged its unreliability. But they credit SHE Teams, a specialized division of Telangana Police established to address women’s safety and security concerns, for helping bring a gradual change to law enforcement’s attitudes towards gender-based violence. However, researchers have noted that although SHE Teams managed to create awareness of crimes against women, their current approach still reflects patriarchal notions of control and surveillance.2

To genuinely address the challenges faced by women, it is imperative for the state to invest in community awareness programs. They can build up on the community-driven efforts employed by organizations like Shaheen as they have the potential to challenge patriarchal structures and norms, paving the way for a more equitable and secure environment for women. Furthermore, funding accessible public transport and decentralizing development efforts in Hyderabad city will have long-lasting effects on the overall well-being of the residents of Old City.

- Making of the Hyderabad Riots by Asghar Ali Engineer – https://www.jstor.org/stable/4397302

- Policing responses to crime against women: unpacking the logic of Cyberabad’s “SHE Teams” by Usha Raman & Sai Amulya Komarraju – https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14680777.2018.1447420